The Complete Guide to Camera ISO for Photography

The Complete Guide to Camera ISO for Photography

ISO is one of the most important concepts to understand if you want to create better photographs, and ESPECIALLY if you want greater manual control over your camera. Adjusting your ISO speed can save an otherwise unobtainable image…or completely destroy your detail if you don’t know what you’re doing.

If you’re searching for a comprehensive guide on what ISO actually is, why it’s important for landscape photography, and when you should (and shouldn’t) adjust it ….then this is the guide for you.

Table of Contents

- 1. What is ISO Speed in Photography?

- 2. Why ISO is So Important in Photography

- 3. What Happens When I Increase ISO?

- 4. How to Minimize Noise from ISO

- 5. When Should I Increase my ISO?

- 6. Summary

1. What is ISO Speed in Photography?

The Definition of Camera ISO

Here’s the simplest explanation: increasing your ISO speed is an artificial way to brighten your photograph without having to change your shutter speed or aperture. We’ll discuss why retaining your aperture/shutter speed is so important later, but for now….just know that ISO is an alternative way to obtain the proper exposure (level of brightness).

Many articles refer to ISO as a way to increase the SENSITIVITY of your sensor to the available light (in other words, to make the sensor absorb more light), but this is incorrect.

The rate of light absorption by your sensor is set by your aperture and shutter speed. ISO can “amplify” this light even further, but it comes at a cost: an increase of digital noise.

It’s a bit like artificially increasing the exposure of a raw file in Lightroom or ACR; yes, your image becomes brighter, but it chips away at the quality when compared to an image that was actually exposed to more light in the field.

So although ISO is part of the “exposure” triangle, it does not influence the actual exposure. Only your aperture and shutter speed control the amount of light that actually hits the sensor.

We’ll discuss the pros and cons of increasing your ISO, and when you should (and should not) adjust it….but for now, just understand that ISO is like an “emergency switch” to pull when you absolutely must increase the brightness of your image to obtain a faster shutter speed and/or deeper depth of field.

The Typical ISO Range

For most professional camera bodies (either DSLR or mirrorless), the ISO range starts at the lowest “base” value. This number will depend on your camera, but most start at 100 and will increase to about 32,000.

A higher ISO number means that the camera is amplifying the light at a higher rate of intensity, making the image appear brighter for a specific aperture/shutter speed combination.

When you double your ISO (i.e. from 200 to 400), you roughly double the brightness for that image.

Native vs. Extended ISO

Before we move on, I should clarify that there is a big difference in image quality between “native” and “extended” ISO.

Native ISO refers to the actual, authentic range for your specific camera – usually 100 to 32,000. “Extended” ISO is a marketing gimmick to make it appear as though the camera has a larger ISO range or is otherwise a good performer in low light, but the results can be disappointing. This is also known as “fake ISO”.

Basically what happens is that the camera will perform some processing to the image in order to reduce the appearance of digital noise…but this can greatly affect the quality of your texture, contrast and colors.

When choosing a camera for good ISO performance, you should always consider the native ISO, and NOT the extended.

This is, again, relatable to artificially adjusting your exposure in post-processing vs. actually exposing the sensor to a different amount of light in the field. Although raw format can give you good quality adjustments, it’s still artificial. You will always have the highest quality when you capture the proper exposure with your sensor.

KEY TAKEAWAY

ISO gives your camera more “breathing room” by allowing you to extend your shutter speed/aperture capabilities. However, this comes at the cost of added digital noise, so you need to weigh your options carefully. Your ISO should always be set to your base native setting (usually 100 ISO), unless you have a specific reason for increasing it.

2. Why ISO is So Important in Photography

A Brighter Image = More Creative Options

If you are able to collect more light from a scene without having to change your aperture or shutter speed to compensate, this means that you will have more leeway with the images you can create.

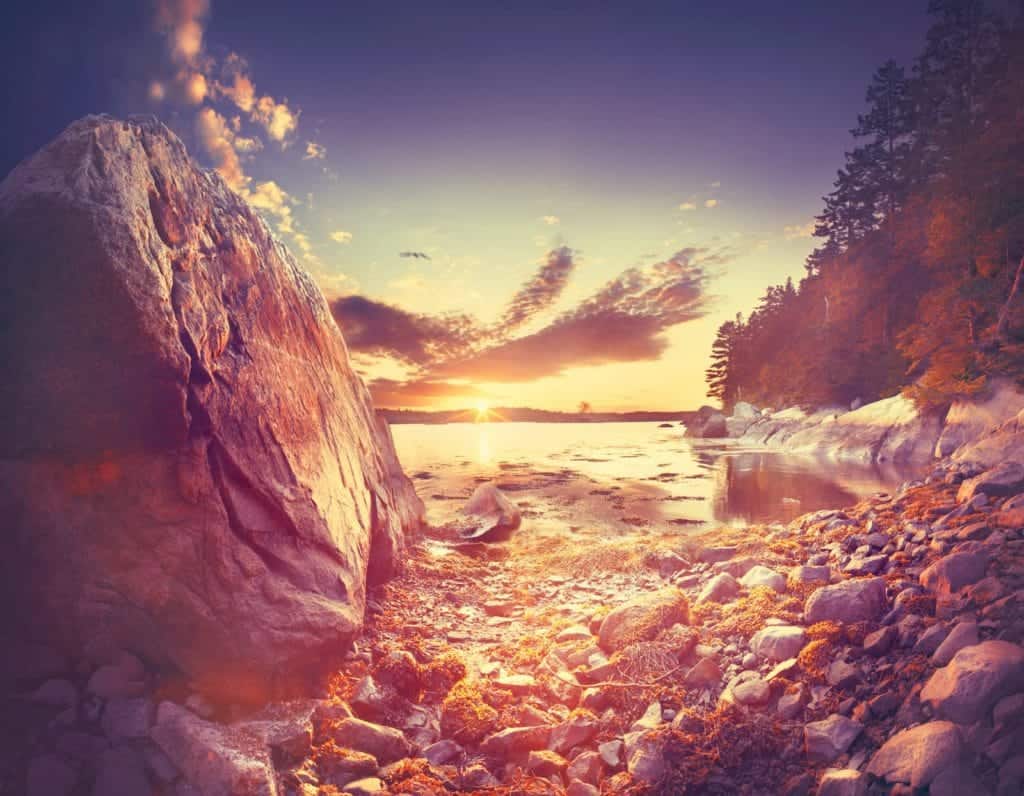

For example…the photo below presented some particular challenges:

(1) The amount of available light was low since this was photographed just at sunset. However, I needed to retain a deep depth of field, so my aperture had to be small (f/16) – which restricts the amount of light hitting the sensor.

(2) The other challenge was my shutter speed: I needed it relatively fast in order to keep some detail in the clouds and reflection in the water. I was using a tripod, so I did not have to worry about camera shake. However, the clouds were fast-moving, so a longer shutter speed would have rendered those too blurry for my creative vision.

The point here is that I could not adjust my aperture or shutter speed in order to properly expose my image.

This is where your ISO comes into play as increasing it will brighten your image, and give you more leeway in your aperture/shutter speed.

By increasing my ISO here, I was able to:

- Retain a deep depth of field with my chosen f/stop.

- Keep my cloud detail sharp and avoid motion blur with my chosen shutter speed.

- Properly expose my frame in the field with my chosen ISO, giving me the highest quality detail possible.

ISO can Help to Freeze Movement

With the images below, I wanted to keep a deep depth of field, but also capture the falling snow. However, since I was working with limited light, I couldn’t reach a fast enough shutter speed to capture the flakes without widening my aperture – which I didn’t want to do as that would make my depth of field more shallow.

My only alternative was to increase my ISO from 100 to 1600, which brightened my image substantially… allowing me to increase the shutter speed enough to capture the falling snowflakes without (1) compromising my depth of field or (2) underexposing my photograph.

Since this was a busy scene with many lighter tones, the pixelation and noise from the increased ISO is barely noticeable – even to the trained eye.

ISO becomes especially useful when shooting handheld, as photographing with slower shutter speeds can blur your detail without the assistance from a tripod. We’ll discuss this more later, but just know that increasing your ISO can allow you to create an image that would otherwise not be possible…

So understanding how to best use ISO is VERY important to your photography, for both technical and creative purposes.

However, before you start increasing your ISO whenever you need a boost of light, there are some important drawbacks to consider. I’ve always considered ISO to be for “emergency use only”….and you’ll see why in the paragraphs below.

KEY TAKEAWAY

If you must have a specific shutter speed and/or aperture setting, and your image is still underexposed (or blurry)…that is where ISO comes in for the rescue.

3. What Happens When I Increase ISO?

ISO Amplifies Existing Noise

First, you should consult your camera manual to see how to change your ISO setting as this will differ from model to model….but typically, there’ll be a button you press and hold, and a dial to turn to change your ISO.

Make sure you are working in manual mode, as adjusting ISO may inadvertently change your aperture/shutter speed to compensate for the increase in brightness.

The trade-off to increasing your ISO in digital photography is that you’ll also be amplifying the “noise” in your image. It’s the camera’s way of making your image brighter without having to absorb more light.

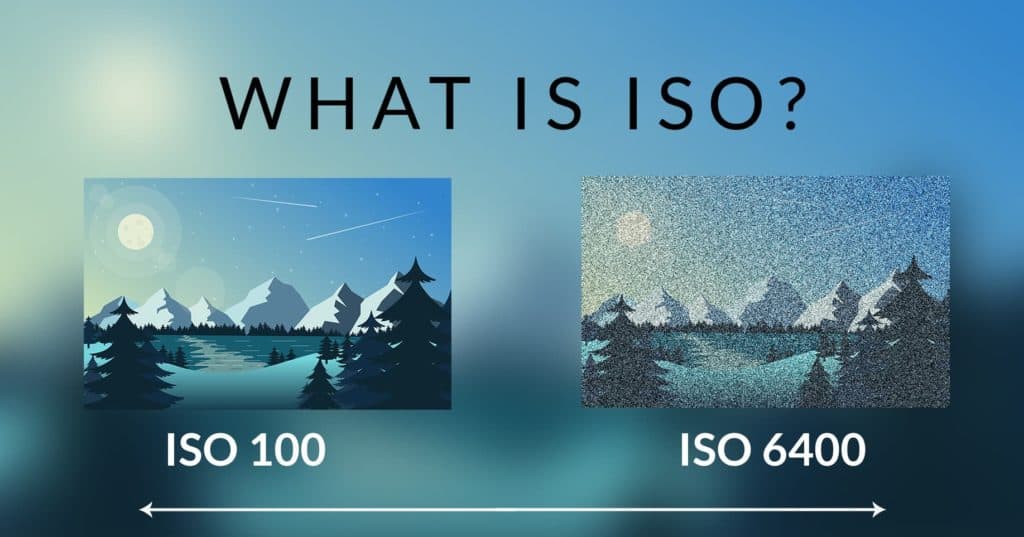

As you can see in the right image below, this is usually an unwanted side effect: random pixels of varying brightness and color that distract from the content.

All images have some degree of noise…but when shooting at your base native ISO setting, you usually can’t see it. This is why programs like Lightroom will automatically add a bit of noise removal when you import your raw files (we’ll discuss noise removal more later).

However, when you increase your ISO in order to brighten the image, the noise is amplified.

I should clarify that ISO is NOT the same as noise. I see the terms used interchangeably with statements such as “my image has too much ISO”, and that’s not technically correct. Noise is a side effect of increasing your ISO, but not all noise is caused by a higher ISO.

For example, noise can also be amplified by artificially increasing the exposure of dark shadows. Very long exposures will also add noise to your image as the sensor heats up.

I should also note that “noise” is not the same as analog “grain”. In film photography (especially black and white), grain is usually pleasing and is used for aesthetic purposes by adding texture to an image. However, digital noise is of lesser quality and appears more pixelated than film grain…and is almost always an unwanted side-effect.

Now this doesn’t mean that increasing ISO will necessarily ruin your image – in most cases, the noise will not be very noticeable or detract from your content. And if it comes down to capturing the photo you want with some noise, and not capturing it at all, I think most will choose to handle the increase in noise.

This is why I refer to ISO as my “emergency switch” – the last resort when all else fails.

However, increasing your ISO should NOT be done without intent and consideration. You need to weigh the pros and cons depending on (1) the characteristics of the scene you’re photographing, and (2) your desired result.

It’s not just about adding noise to your image. It’s also about degrading the overall image quality – specifically, the apparent sharpness of your local contrast and the overall purity of your colors.

Is it Okay to Have Noise in my Photos?

The short answer – yes. It depends though.

So, you’ve increased your ISO and now you have digital noise to deal with. Whether or not this is a big problem or just a minor inconvenience depends entirely on the image; the texture, color, and luminosity all have a role to play in how strong the noise appears.

The first thing to consider when setting your ISO is the actual subject matter…the content of your image. Noise from an ISO bump is not always going to look the same at a given setting (let’s say 800 ISO) depending on the amount of local contrast (texture and detail) in your frame.

Noise is more apparent on darker tones (shadows), and when there is little variation in the tones themselves. In other words, low-frequency detail that lacks local contrast and texture.

For example, a photo of the night sky with a high ISO will produce some noticeable noise across the sky – both because of the darker tones, and because the sky has little variation in contrast to help “hide” the noise.

In the close crop below, you can see the pixelation and general blotchy texture of an empty sky that should be smooth and seamless.

Combine this with the fact that ISO becomes more apparent the longer your shutter is open (due to heating up the sensor), and you’ve got the perfect storm for a high-noise image.

This is why astrophotographers are always on the lookout for camera bodies that handle noise particularly well…because in order to capture a photo in sharp detail where the available light is severely limited, you have to bump up that ISO quite a bit.

However, if you were photographing a “busy” scene – such as the snowfall image below – the digital noise will become lost and be hard to notice. You can see that there is no noticeable difference in noise between ISO 100 and ISO 1600.

The noise is still there in the image, but the texture and contrast help to hide the noise, so it doesn’t become a distraction. The only noticeable difference is the movement of the snowflakes being frozen by the faster shutter speed.

Here’s the point…if you do find yourself needing to increase your ISO, the goal should be to find the right balance between (1) what is an acceptable amount of noise and (2) retaining detail while exposing your image properly.

I get questions like “Should I ever increase my ISO?” or “Should I always shoot at the lowest ISO setting?”…which really aren’t the right questions to ask. The answer depends entirely on (1) the quality and condition of your environment, and (2) your goals for the image, both technical and creative.

What is the Best ISO Setting for Landscape Photography?

Now when it comes to landscape photography, increasing your ISO should be your last resort. Since we are typically using a tripod to stabilize our cameras, unintentional motion blur becomes an obsolete reason to increase ISO since we are not photographing while handheld.

However, if you have creative or aesthetic reasons for retaining a specific f/stop and/or shutter speed and you need to brighten your image a bit to bring it up to the proper exposure….then you can start debating whether or not to increase your ISO.

It’s important to mention that technology has made leaps and bounds over the past few years when it comes to improved ISO performance, as camera manufacturers have listened well to the needs of low-light and night photographers. Not too long ago, a photograph of smooth texture taken at 1600 ISO or higher would be completely unusable…but now, you can achieve great results with a bit of noise removal.

KEY TAKEAWAY

ISO will amplify the existing noise in your image…so depending on the content, the noise may be barely noticeable or extremely distracting. The goal is to find a pleasing balance between (1) what you want to achieve, and (2) the limitations of your gear – and whether or not the side effects of a higher ISO is worth the result.

4. Minimizing Noise from ISO

Removing Noise in Post Processing

Speaking of noise removal, you’re probably aware already that you can lessen the appearance of noise later in processing. Lightroom is my favorite program for removing noise since you have a great amount of manual control over both the quality and accuracy of your noise removal attempts, where other programs tend to automate the process and the results can be hit or miss depending on the content.

You should be aware that removing noise will soften the texture and contrast of your image. Since you’re effectively removing sharpness to counteract the noise, this can degrade the quality of your photograph.

This is why it’s ideal to avoid noise altogether, since intense noise removal can actually make your image less appealing than if you just left the noise in and dealt with the distraction.

With that in mind, noise removal should only be used when necessary…which means that the noise is overly distracting or otherwise detracts from the story you’re trying to tell.

There is an exception though. If you’re removing noise from an area where sharpness is NOT important (such as the empty night sky above, or still water), then noise removal will only help your image since you don’t have to worry about retaining texture.

This is why noise removal software is most powerful when you have the option to control the strength of it locally. In other words, you can choose WHERE in your frame to apply noise removal to, and where to exclude it…and can apply it at different levels of intensity.

For example, in the image above, I don’t have to worry about retaining sharp texture and contrast in the sky or most of the reflection in the water…so I can be quite heavy with my noise removal there. Thankfully, smooth texture like this is also where noise is most obvious.

However, if I applied the same strength of noise removal to the rocks and sand in the foreground or the tree line, that would greatly affect my texture and contrast and make the image appear soft and fake. Fortunately, noise is hidden well in high-frequency areas like this so I don’t have to worry about removing it from those areas.

Lightroom has a fantastic feature for removing noise locally and will automatically apply it more heavily to low-frequency, smooth areas…while attempting to retain contrast and texture along sharp edges.

Sensor Size and Noise from ISO

The size of your camera sensor also controls how obvious the noise is for a given ISO setting. The larger the sensor, the more “breathing room” the pixels have around it…and thus, the noise produced is less obvious.

This is not to be confused with megapixel size, which is how many pixels are packed within a specific sensor.

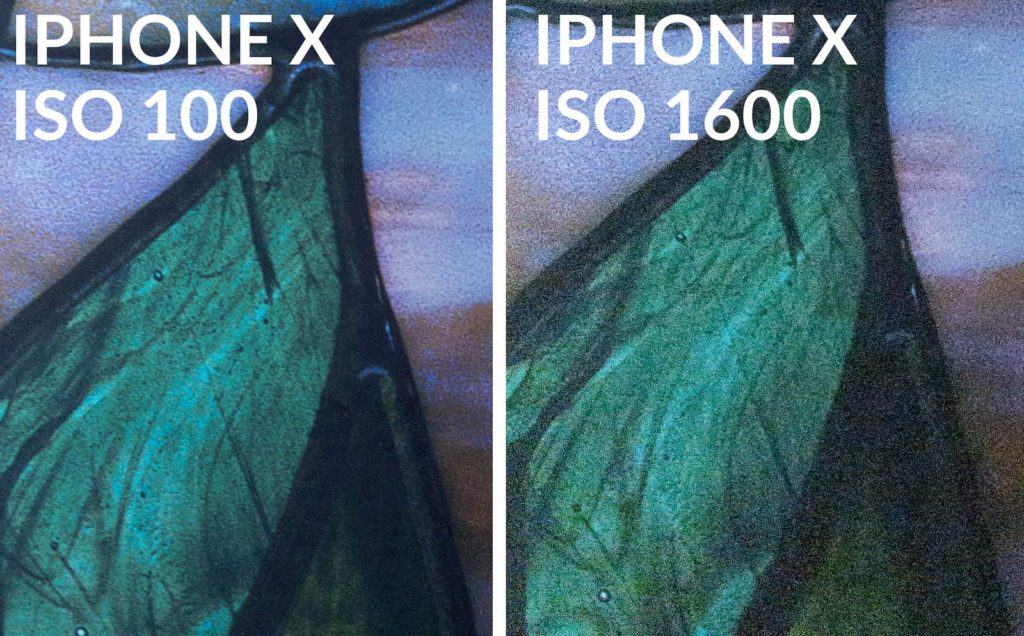

ISO performance and noise is one severe limitation to iPhone photography…the very small sensor size will give you noisy images at higher ISO settings.

In the images below, you can see the difference in noise, sharpness, and color purity between ISO 100 and ISO 1600 for the iPhone X.

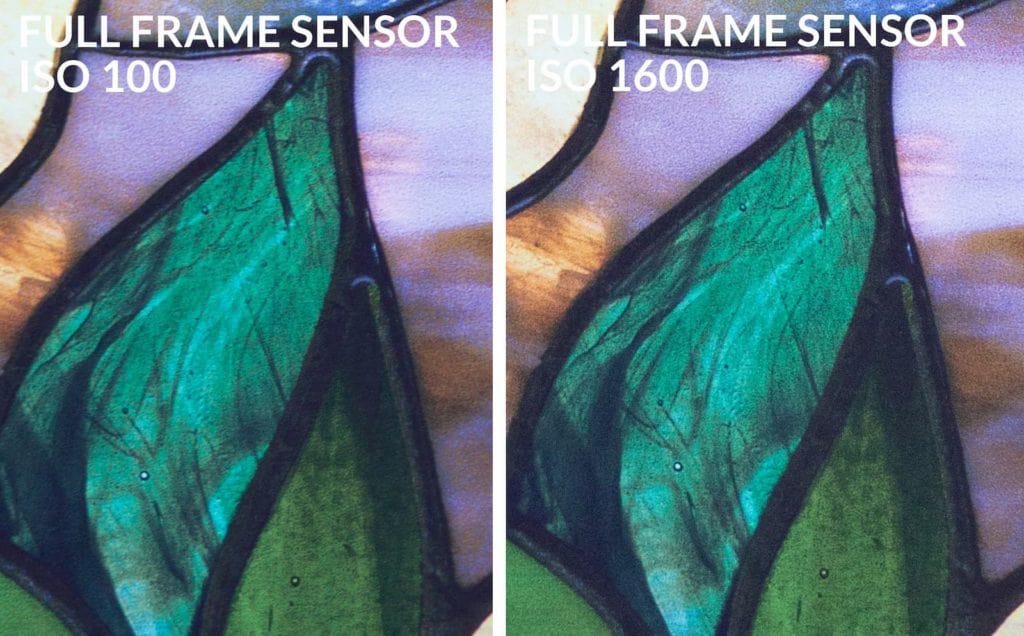

However, on a mirrorless or DSLR camera with a much larger sensor, the noise is much less noticeable when comparing the same ISO settings. For the comparison below, I used a full-frame sensor.

Currently, there’s just no way for compact sensors on phones and tablets to compete with the much larger sensor size of mirrorless or DSLR camera bodies.

On another note: downsampling will also reduce the appearance of noise, which is why JPGs uploaded to Facebook or Instagram often appear noiseless.

KEY TAKEAWAY

Removing noise comes at a cost: softening of detail. However, whether or not this is detrimental to your image will depend on the content. Smooth texture can handle heavy noise removal, while sharp texture can only take a little removal. If you have a lot of noise, don’t try to remove ALL of it…but just enough where it’s not a distraction.

5. When Should I Increase my ISO for Landscape Photography?

General Recommendations

First, I recommend to never use auto ISO. It can be helpful when you’re not sure what ISO setting to use for a given aperture/shutter speed…but more often than not, you’ll forget to turn this feature off before your next outing. Which means you may inadvertently ruin a perfectly good photo with excess noise, and/or have no control over your shutter speed and you don’t know why.

For me, I do a lot of long exposures so it’s just not worth the hassle of turning it on and off, so I always adjust my ISO manually – and only when I require it.

If you’re using a tripod, and your shutter speed is not a factor, then your ISO should always remain at 100 (or whatever your native base ISO is) for the highest quality detail and maximum dynamic range.

However, there still needs to be enough environmental light absorbed by the sensor at your chosen shutter speed/aperture combination. Purposefully underexposing the image in order to capture it at ISO 100, and then artificially increasing the exposure in processing does not always give you the best image quality. Even in raw format, this will sometimes produce WORSE noise in your deeper shadows…and also, you may be missing out on capturing the original texture and color purity in the field.

The point is that there is no concrete answer as to whether or not you should adjust your ISO; you need to evaluate your environment and the ISO performance of your camera to determine whether or not you should bump up your ISO.

Increasing ISO for Handheld Photographs

Of course, if you ARE working hand-held, then increasing your ISO becomes a more common requirement…since a slightly noisy photograph is usually preferred over blurring out the detail altogether from camera shake.

If you find yourself in a low-light situation without a tripod (i.e. indoors or during the twilight) where you’ve opened your aperture as far as it will go and still can’t get a sharp enough image (or you want to stay at a certain aperture for creative effects), then it’s well worth increasing your ISO in order to capture the moment.

Let’s say you’re photographing under little available light (like in the image below) and you have to work handheld. You can’t widen your aperture in order to retain a deep depth of field; compromising that would produce much softer detail in the background trees, which would ruin the photograph.

The alternative here is to increase the ISO and deal with a bit of added noise. Since there is much texture in the scene, the noise will be hidden well….and any small areas of smooth texture where noise is apparent can be removed easily.

Focal length also plays a role here when photographing handheld. Longer lenses require a faster shutter speed to avoid camera shake – typically twice as fast as the longest focal length for that lens. So for a 24-70mm lens, the slowest shutter speed you could use to capture a sharp photo while handheld would be 1/140th of a second…rounded up to the nearest shutter speed of 1/250th of a second.

If you like wildlife photography, then you will find ISO to be particularly helpful here. When tracking birds or other fast-moving subjects, being tied to a tripod is often not an option…so camera stabilization becomes a very important factor.

To exacerbate the stabilization problem even further, you will often be (1) photographing with a very long lens, and (2) need a very fast shutter speed to freeze fast-action movement from wildlife. This means that even with ample amount of available light, you will probably still need to increase your ISO.

This is why wildlife photographers will often search for a camera with extraordinary ISO performance so they have the most leeway with their shutter speed.

Increasing ISO for Mounted Images

Even if your camera is mounted to a tripod (thus eliminating any movement from camera shake), you’ll still find yourself in situations where an ISO bump is needed to retain your creative vision for an image….the aesthetic effects of a specific shutter speed and/or aperture.

For example: if you want to freeze movement under limited available light, you’ll probably have to increase your ISO a bit so you can properly expose the image at a fast shutter speed.

Or perhaps you’re photographing moving water and you found a nice shutter speed sweet spot that retains some texture, like in the image below.

I wanted to create streaks of water around the rocks as the tide receded. A slower shutter speed here would have blurred the water out too much and eliminated that nice wave texture, but a faster shutter speed would have created sharper lines and contrast, which I did not want. The shutter speed here was just what I was looking for.

Also, I wanted good foreground to background sharpness, so my aperture needed to stay small for a deep depth of field.

If I had a lower amount of available light here and my image was underexposed, I would need to increase my ISO a bit to get the proper exposure without having to compromise my depth of field or my shutter speed.

As mentioned earlier, astro and night photography will often require you to use a high ISO in order to capture your image within a reasonable amount of time. In the image below, I used a very wide aperture (f/1.4) and a tripod, but even with that massive aperture letting in as much available light as possible, my shutter speed was well over 300 seconds and STILL underexposed.

In retrospect, I should have increased my ISO a bit to properly expose the image in the field instead of artificially increasing the exposure in post-processing. This would have given me the highest quality detail.

KEY TAKEAWAY

Generally speaking: you should always keep your ISO at the base native setting – usually ISO 100. If you’re shooting handheld, need to freeze fast action, and/or shooting at night… the decision to increase ISO will be more common. However, if using a tripod and/or there is little movement in your frame to compensate for…you will rarely need to increase your ISO.

How to Choose the Best ISO for Your Landscape Photograph

When in the field, this is how I generally approach a scene and decide whether or not I’m going to increase my ISO above the base setting.

First, I move into aperture priority mode and select the right f/stop for my desired depth of field. For me, this is the most important choice for landscape photography.

Next, I decide what shutter speed is necessary for that depth of field. Usually, I’ll see what the camera thinks the optimal shutter speed should be for a given aperture as this at least gets me in the general vicinity, and then I’ll use my histogram to fine-tune if needed.

However, if I require a certain shutter speed for creative purposes, that is when I may pull the “emergency switch” and increase my ISO. If there is too much light hitting the sensor for a given aperture/shutter speed, I’ll attach ND filters. If there’s not enough light, I’ll bump up my ISO.

My process may vary a bit depending on the unique challenges and goals for an image, but this is the general workflow I follow.

6. Summary

You can see how your ISO, shutter speed, and aperture work together to create what is called the exposure triangle. If you increase your ISO, you make the image brighter for a given shutter speed. If you change your shutter speed, you increase or decrease the amount of time that the light is exposed to your sensor – which means that you need to either widen or close your aperture to compensate.

Alternatively, if you adjust your aperture for a different depth of field, you need to change your shutter speed to compensate for the increased or decreased amount of light let in through your lens.

In short, all three settings work in harmony to create the exposure you want – you can’t adjust one setting without changing another if you want to maintain the same exposure – or level of brightness.

Lastly, I would recommend that you test the ISO performance of your specific camera body, as the quality can vary greatly from model to model. Photograph a smooth (low-texture), dark subject and increase your ISO for each frame, making sure to use a tripod for stabilization.

This will give you a clear representation of how much noise is present for each ISO setting…and you can decide your maximum tolerance level now without having to do test shots in the field.

Christopher. I am really am appreciating this new format. I especially like Key Takeways along with the personal comments and advice, which as always, is supported with your reasoning and excellent explanations. ISO is my first topic visited after your rework. Feedback: You have my tick of approval for delivering a package that is full, informative and is to become my source of both practical reference and a personal guide.